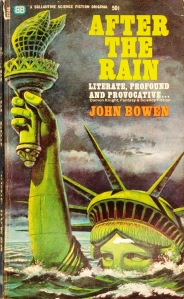

After the Rain by John Bowen

Ballantine Books, 1965 (Second edition)

First edition published in 1959

Price I paid: 75¢

The British are a hardy island people. At least two aspects of this country are world-renowned—the astonishing number of high calibre writers they produce, and their climate.

AFTER THE RAIN is an impressive combination of both. In fact, Angus Wilson says:

“If you like cataclysmic novels John Bowen’s AFTER THE RAIN is as exciting as any deluge you can hope to find: but if you think deluges are twoo trivial, John Bowen has a surprise for you: his novel turns out to be a satire of the first order.”

I’m going to be honest, it’s very hard for me not to make this entire review a single image of me with an uncomprehending stare. Maybe a gif? Maybe a rotating gallery of images, in which I occasionally appear, but mostly recognizable features from popular culture.

Who am I kidding? It’d all be Homer.

Good night, everybody!

Okay, just kidding. I’ll save that gag for another time.

You know what’s great? When I post a link to this blog post on Facebook and Twitter, I know for a fact that the preview image will be Homer and there’s absolutely nothing I can do about it.

It certainly seems like I’m having trouble getting around to describing this book, doesn’t it? Wanna know why? It’s not surprising at all, but it’s because I’m having a lot of trouble even figuring out how to start. I’m having trouble remembering basic facts. I don’t remember a lot of what happened, and what I do remember doesn’t fit together into much of a sensible narrative.

Up top you’ll see Angus Wilson saying that this book is a “satire of the first order,” and maybe that’s true, but if it is, it’s a satire of stuff from sixty years ago and I clearly don’t get it. The alternative is that it’s a satire of stuff that’s always relevant and it’s either poorly told or my brain doesn’t recognize it. Those are possibilities and if someone at any point wants to step in and say “Thomas, here is the key point you missed,” I’ll be quite grateful.

There are some characters in this book, and if pressed I might be able to tell some of them apart, but I wouldn’t count on it. There are some names and behaviors and I suppose that some of them go together. Even the narrator main character is a sort of void to me whose name I didn’t learn until almost halfway through the book.

Said main character is Mr. Clarke. I think his first name is John, but that comes up even less than his surname. In a way that makes sense. It’s a fun game—I think I’ve mentioned this before—to note when and how the author finds a way to deliver us the name of the first-person narrator. Is it in dialogue? How clunky is that dialogue? Is it on the first page? Is the very first line of the book something like

“Steve, welcome to the freedok academy!” the instructor said to me when the simulation ended.

or

I woke up with a splitting headache. Oh crap…who am I? Let’s take this one piece at a time. I’m on a freedok ship. I’d certainly never be able to forget that. My name is…Stan? Steeb? Sterbo? Sting? Starv? Sbeerp? Steve!

My personal favorites, and this is me being serious for a moment, are the ones like

Hey! I’m Steve.

I know there are a lot of ways to write a book and they don’t all have to be to my exact specifications, but a first-person narrative works a lot better for me if the narrator has got some personality and a voice of their own. I want to feel like I’m in a conversation with that narrator.

After the Rain does not do that. Our protagonist either gets his name somewhere deep in the book, or it’s mentioned early on and I don’t have enough giveacrap to notice. While sometimes we delve into his emotional life, it’s dull and unenlightening.

The very beginning of this book has some promise. Mr. Clarke writes magazine copy, and within the first few pages of the book he meets a guy named Mr. Uppingham. Clarke figures he’ll follow Mr. Uppingham around for a little bit, since Uppingham is a self-professed rainmaker. The pair go to a drought-ridden Texas, where Uppingham rides a balloon up into the air and does something mysterious. A bright flash of light brings Uppingham’s balloon back down to Earth, killing him. Within minutes, rain clouds start to gather and the rain starts not long after that.

The thing is, this rain isn’t confined to Texas. It’s worldwide. What we’ve got is a new universal deluge, a Noah II situation, and it’s rough times.

Up to here I’ve been following the book pretty well. There were only two or three characters and while they were pretty flat I was at least able to keep them separate. John returns to England where, like everywhere else, it’s raining constantly. He meets up with his friend Bob, who asks him to take his (Bob’s) wife, Wendy, to a camp on something called Chew Hill. So Clarke and Wendy set out. On the way there they meet Sonya, a dancer, and she and Clarke begin to fall in love at some point. Wendy dies at camp, so Clarke and Sonya leave again. Not long after, they come across the Raft.

This is where I started to have trouble.

There are seven or eight other people on the Raft and they all ran together in my head so that I couldn’t tell what was happening to whom or why I should care. This book certainly isn’t unique in this regard, but it stood out for some reason. Maybe because I was on constant lookout for something that might be a “satire of the first order.” Over time I started to wonder if that was indeed the satire, the fact that these people were all indistinguishable?

It’s as good a guess as any. I never once learned what this book was satirizing. Herd mentality, perhaps. Later there’s a bit of Cult of Personality stuff going on that might be relevant, and goes hand in hand with the other thought.

This may be where the whole thing as a satire fell apart for me, and it’s a matter of the time gap. Perhaps sixty years ago a story of people following a charismatic leader would be a bit more shocking. Now it’s routine.

I realize I haven’t gotten to that point yet. See, there’s a character on the Raft named Arthur, and he’s the leader. Everybody defers to him and he gets angry when other people come up with ideas that he didn’t or suggest that he modify his plans. Okay, fine, I guess.

The thing is, if this is the point of the “satire,” then it doesn’t help that it doesn’t really go anywhere. Arthur gives orders and people follow them, but ultimately they’re not, um, evil or anything. At least not at first. They’re not self-destructive orders, or dumb, or anything. Later that changes, but it happens exactly once before someone rebels against him.

The rain stops about halfway through the book. Arthur decides that since it’ll be the purpose of this group of people to repopulate the Earth, and that their lives and the stories of their survival will be passed down to all future generations, that it would be smart to go ahead and start the mythology-building process right now. So they do. Arthur deems himself God.

Meanwhile, Clarke is fighting back the bitter taste of jealousy. His lover, Sonya, has been spending a lot of time with another guy on the Raft, named Tony. Tony is a bodybuilder and he spends a lot of his time working on those gains. Sonya spends time with her because she’s also a physical-type, a dancer, and she needs to work out too. So Clarke decides that they’re probably having sex.

Maybe this is a satire of toxic masculinity, because if Clarke had just, y’know, tried to talk to either Sonya or Tony about the situation a lot of this book would have been avoided. And it’s a lot of book that could definitely have been avoided because it didn’t really have much at all to do with any of the rest of it. Maybe it was an attempt to imbue this story with some kind of emotional resonance, but it failed, because all I could think was that our main character was just being a jealous idiot.

There’s a fair amount of heterosexual jealousy in this book. At another point two of the women on the Raft get into a fight over which one has been properly “possessed” by the God Arthur. Bowen’s Wikipedia page points out that he was a gay man, so now I kind of wonder if he’s not poking a little fun. I’m fine with that.

Then again, according to the Wikipedia page, Bowen met his partner of 52 years after this book would have been written, with no indication of his sexual preferences outside of that, so I suppose it’s anyone’s guess as to whether it has anything to do with this book.

That page needs some cleanup work and reads like it was written by a fan or a family member or perhaps both. The man himself seems to be quite interesting, working as a noteworthy playwright and author for most of his life. This book appears to be one of his few forays into science fiction, and honestly it’s hard to say that this book is science fiction. It’s a book where it rains a lot due to a scientific incident, sure. We could argue over it, but it’d be pointless, so let’s not.

The Sonya/Tony thing turns out to be a nonissue when it turns out that Tony is “unable to perform.” He might be gay (although he denies it), or asexual, or any other number of things that really shouldn’t be shameful but are to him, but whatever the case may be, he’s dismayed to state that despite all the women who throw themselves on his magnificent bodybuilder physique, he’s never been able to make it with any of them.

What does this have to do with anything? I don’t know. It does mean that Clarke realizes what a silly dumb guy he’s been. Fine, whatever. It also means that Sonya’s growing fetus (oh yeah, she’s pregnant, incidentally) deffo belongs to Clarke.

Arthur declares that God Arthur has ascended into Heaven and the human left behind is to be His prophet. At another point the boat denizens see a giant squid in the water, and Arthur says that it is God in one of His manifestations.

The book’s getting close to ending at this point and I still don’t see what any of the point is.

Finally Arthur declares that a sacrifice is needed. Once this happens, the Raft will find somewhere to land and civilization can restart. Arthur decides that it should be Sonya’s baby, once it’s born. Clarke is fine with that at first, as long as it means that Sonya is kept safe. Tony, on the other hand, hears about it and declares that child sacrifice is over the line. He fights Arthur, they tumble into the water to be eaten by sharks, and then land is spotted, and that’s the end.

I think what I was supposed to get out of this book was a tale of people under pressure dealing with the situation at hand and each other. Perhaps a series of character studies? Perhaps a microcosm of Western Civilization? I don’t know, and a large part of why I don’t know is because, like I said, these characters completely failed to distinguish themselves in my mind. One character, I’m pretty sure, vanishes, and I only just realized that. Another one dies and I did notice that one, but it took a while.

I’m making it sound like this book was utterly crummy, but I can’t go all out and say that. The text of this book was actually quite fine in a stuffy late-50s British kind of way. In a lot of ways I think that’s its main problem: I have a lot of trouble getting into similar books from this time period and point of origin. Perhaps it’s a personal failing or a simple matter of time and place.

So this book might be completely up your own alley! I can’t say that it wouldn’t be. But it didn’t work for me.

Bowen adapted the work into a play, and maybe that would be better for me. Perhaps if I could see the action and hear some voices I’d be able to tell you what, exactly, this whole thing was supposed to be about. But since it ran together in my head so much that bits and pieces are forgotten and the rest is all the same narrative weight, I can’t tell you. I’m doing the book a disservice, I think.

It’s like, I do enjoy the occasional Wodehouse novel, but I run into this problem there too. At least with Jeeves and Wooster I have two characters to anchor myself on (plus the occasional Aunt Agatha), but a lot of the other folks do run together for me because they’re all wealthy twits. But I love the Stephen Fry and Hugh Laurie series, where I have little to no such trouble.

There is, of course, the distinct possibility that After the Rain is just bad.

I’m reading reviews on Goodreads and elsewhere and they are strongly divided. Lots of people seem to react the same way I’m doing so now, a few are staunchly defending the book. I think that’s interesting!

The front cover is a giant lie, though. Surprise surprise, a British book has been repackaged to distract potential readers from its incredible Britishness. The back cover sure doesn’t do that, though! There’s no summary, so it can’t be a pack of lies, but it sure does talk about Britain more than it does the novel.

In a way these two things might sum up my feelings about this book. I don’t think it knew what it was trying to say, or to whom it was trying to say it. This was only Bowen’s second novel in a long life of writing.

I don’t think this book was a satire at all. I feel like a satire should at least have a point to make. A vague point like “people sure are funny sometimes” is enough! After the Rain didn’t even go that far. Perhaps it wasn’t meant to be a satire and it just got saddled with the term, leading me to have false expectations, so that now my disappointment and confusion are here not because of the text but because Angus Wilson decided to misapply a term.

I don’t know! Anybody else read this one? I’d welcome any elucidation.

British, huh. Too bad, I liked the cover.

Your post intrigues me. Bowen certainly seems to be poking fun at Noah, and who could resist such low hanging fruit. The squid seems like a dig at Moby Dick. Maybe Angus Wilson said parody, not satire, and the blurb got it wrong. Blurbs do that, you know.

Maybe the Texas scene was Bowen poking fun at The Rainmaker. He was a playwright, after all. “See what trouble we would all be in if Starbuck was for real!”

Then “God” demands the sacrifice of a girl child. You may think of Abraham and Issac, but I remember Jephthah and his unnamed daughter in Judges 11, because he actually sacrificed her. Gender equality was already missing way back then.

You’ve made me waste twenty minutes scratching my head, but I’m still not going to read the book. That’s what Schlock Value is for.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To quote a title by Vaughn Bode,

“RIFF-RAFF ON DA RAFT”

LikeLiked by 2 people