Streetlethal by Steven Barnes

Streetlethal by Steven Barnes

Ace Books, 1983

Price I paid: 90¢

Los Angeles is a teeming metropolis with a rotten core: Deep Maze, where the Thai-VI ghouls—the disease-spreading Spiders—roam. Here the all-powerful Ortegas rule over their empire of drugs, prostitution, and black-market human organs “donated” by their helpless victims.

All Aubry Knight, the former weightless boxing champion, wants is to be left alone. But you’re either with the Ortegas or against them, so they made his life a hell. First they tried to control his mind, then they tried to reduce him to “spare parts.”

What says Easter better than an almost-superhero fighting for his life in the ruins of Los Angeles? Not a damn thing!

Folks, this book was a surprise and a half. I didn’t expect this book to be good. I barely expected it to be readable. It looked goofy and probably dumb. But I was wrong. Boy, was I wrong. This book was great writing. Excellent writing, even. I can hardly believe it. This was the work of an actual writer who knows how to construct a story.

For one, this thing was three hundred pages long. I actually had to plan out my reading because if I’d spent my Saturday doing it like I normally do, I would have spent the entire day doing nothing else. Sometimes that happens anyway, but usually it’s because I can’t concentrate on whatever drivel is being pounded into my head. This time, though, it was because of length and plot density. Is that a term that other people use? It makes sense to me. I’ll try and explain it.

I mostly read books that are about half this length. This is for two reasons. Mainly it’s because that’s about how long pulp sci-fi paperbacks tend to be. I would guess that in terms of word count they average somewhere between 50 and 75 thousand words. What tends to happen, though, is that those books have so little plot that they are mostly padding. Maybe ten to twenty percent of an average (bad) sf paperback is the actual story.

In the case of Streetlethal, though, it turned out that this 300 page tome of a paperback was all plot. When things happened, they mattered. It wasn’t even a strict A leads to B leads to C kind of thing. This was the kind of plot where even when you’ve gotten down to R or so you’re still getting echoes from A. Perhaps a better way of putting it is that yes, A does lead to B and so forth, but A, B, C, and D combine to lead to, say, M.

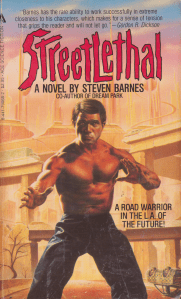

Let’s talk about the cover for a moment, though. We’ve got some kind of Bruce Lee looking guy. He’s poised for action. He’s also got perfect hair, which is impressive considering that he just flipped that car on the right and broke all those highway bridges. Good for him.

He’s not in the book. Our hero, Aubry Knight, is an extremely large and muscular black Adonis. His race doesn’t actually come up all that often, it’s just mentioned in passing a few times. I don’t think his hair was described.

According to the back of the book, Aubry is a “former weightless boxing champion,” but I don’t think that’s true. Yes, he is into zero-gee boxing, which is totally cool, but I don’t think he was any kind of champion. I think he was actually waiting for his big break. Still, he’s amazing at it and the training for it makes him basically a superhero. The book doesn’t describe zero-gee boxing all that much, but it does establish that it takes a certain set of skills different from regular old boxing. Most notably, it requires speed more than strength. To demonstrate this, at one point Aubry drops a piece of paper and then flicks his hand out at it, almost too fast to see. The paper floats down to the ground as if it weren’t disturbed at all, but once it hits the ground we’re allowed to see that there are three holes in it where he’d punched his fingers through.

That’s awesome.

Aubry starts off the book by being sent to jail. He’s set up by a crime syndicate called the Ortegas, whom he works for. Jail is rough. He’s expected to continue working for the Ortegas while he’s in there, primarily via the warden who himself is in their pocket. There’s a thing where prisoners can “donate” their body parts to organ banks in return for shortened sentences, and they try to get Aubry to “help them donate” via intimidation and assault. He refuses, the authorities turn on him, and life is made harder.

Specifically they put him through some kind of brainwashing that makes him feel nauseated whenever he gets angry. It puts a real damper on his skills, since anger is his main motivation. It stops him from fighting nearly as effectively.

I thought this was interesting. For a while I assumed it was just an arbitrary setback that kept Aubry from being too powerful and hurting the plot, and in a way that’s pretty true, but I enjoyed the way he learned to work around it. Instead of finding the people who did it to him and getting some kind of antidote, Aubry meets a guy who basically helps him realize that anger is destructive and that while he can still fight, he needs to do it dispassionately. That’s a bit later in the plot, though.

A major development is that the Ortegas have developed a drug called Cyloxibin. It has some very interesting effects, namely a sort of short-term telepathy that becomes even more expressed when people take it before having sex. Sex becomes something like an ecstatic merging of consciousnesses. It’s also addictive.

Aubry breaks out of prison and goes after the Ortegas. On the way he meets a beautiful woman named Promise, who is an exotic dancer and a prostitute. She also has special skin implants, called Plastiskin, that light up in pretty colors, enhancing her desirability. Twice in the book she manages to use this enhanced skin to blind people. That was also cool.

Promise and Aubry have a dysfunctional relationship at first. They don’t trust each other, both are selfish and paranoid about anybody who might try to help them, and so forth.

In fact, I think one of the stronger elements of this book lies in the fact that Aubry is not a nice person. He is, in fact, an anger-filled muscleman, barely literate, interested only in fighting and single-minded revenge. Normally I wouldn’t be interested in that kind of character but somehow he was also sympathetic. He did have a streak of honor running through him, that’s true, and he was also sent to prison on false pretenses, but on the whole he was just an unlikable jerk.

Together they take down the leader of the Ortegas, Luis, but in doing so put his younger brother, Tomaso, in power, which turns out to be the wrong move. Tomaso is a lot more ruthless than his older brother and verges on the psychotic. When he takes Cyloxibin for the first time, he goes nuts and kills the woman he’s with, but because of the telepathy he experiences her death along with her, and this drives him insane.

Aubry and Promise go underground to hide from the Ortegas. They end up going to the ruins of central Los Angeles. See, right around the same time that Aubry got busted there was a gigantic earthquake that brought LA to its knees. Incalculable destruction. There are, however, still some people who make the best of it. They’re Scavengers, led by a pretty interesting guy named Kevin Warrick.

This part of the book is a combination of the Yoda training montage and the Hakuna Matata sequence. The main plot sort of drops off while our heroes are no longer in danger from it, although the narrative does jump back and forth between them and the villains enacting their terrible plans. Meanwhile, Aubry gets a lot of lectures about survival and human decency from Warrick, a guy who probably has some kind of psychic powers although it’s never delved too deeply into. He’s certainly got something going on, and on several occasions he predicts the future, but he’s also something like a Shaolin master to Aubry, giving him all kinds of Zen bits that go like

Who are you?

I’m Aubry Knight.

That is your name. Who are you?

I fight people.

That’s what you do. Who are you?

I’m looking for revenge.

That’s what you want. Who are you?

And so on. You’d think that kind of thing would come across as hokey or platitude-y, but I think it worked pretty well. Steven Barnes is apparently really big into martial arts, and in a lot of cases it shows that he’s looked into Eastern philosophy in more than a “I want to get kickpunchy” way, which came across in this particular character. I appreciated that.

It turns out that Cyloxibin is grown from a strain of mushroom that Promise happens to have on her due to a plot point I forgot to mention. The Ortegas don’t know that and assume it’s a lab chemical, so that’s why they haven’t managed to make more of it yet. She helps a Scavenger named Emil grow the mushrooms and then gets addicted to them. There’s a dark period where she and Aubry enter this toxic relationship based entirely on the effects of the mushroom and sex. Finally Warrick fixes the problem by whipping Aubry’s ass in hand-to-hand combat. Given that Aubry’s entire persona is based around being able to kickpunch people better than anyone else, it starts to crumble his ego just enough for Warrick’s philosophy to creep through. Thus we have what is probably the least static main character in any book I’ve reviewed up to this point.

Things start to improve until they stop improving and everybody dies. It turns out that the Ortegas planted a tracking device on Aubry that failed to work as long as he was underground. One day he took a step outside for some fresh air and then everything goes to hell. The Ortegas show up in the Scavenger tunnels, fill them with gas and bullets, and take Aubry and Promise prisoner.

It turns out that the real power behind the Ortegas is a blind, crippled old woman named Margarete. She’s Tomaso’s great-grandmother, the matriarch of the family. She’s been running this crime syndicate for something like eighty years.

(Incidentally, this book takes place somewhere in the 2020s.)

Promise reveals evidence to the effect that Tomaso actually killed Luis to take over the syndicate, which drives him even more insane. He tries to kill our heroes, threatens Margarete, and then runs off.

And then Aubry doesn’t kill him. He forgives him. This is partly to do with the fact that Aubry and Promise took so much Cyloxibin that it made them telepathic with each other, although in the final moment that psi power springs forth from Aubry, connecting him with Tomaso, and giving Tomaso just enough clarity that he sees the terrible things he’s done and collapses in guilt and agony.

Holy crap did I not see that ending coming.

I didn’t feel like it was goofy or anything, either. Like so much of this book, it actually made sense in context. There was something about how the Cyloxibin has effects that, to put it one way, makes them more of what they already are. I guess it turns out that deep down inside, Aubry was actually a good guy with a lot of empathy and it took the drug to bring that out in him. It also turned out that the brainwashing at the beginning of the book, which disabled him when he felt anger, actually caused him to put aside his feelings of anger and revenge just long enough to develop into a decent person. Since the book was sort of hinting at that for a good while, the ending felt right.

The epilogue concludes with Aubry and Promise deciding that the best thing to do with this mushroom is to plant it all over the world, free for the taking, so that people can experience it and grow together.

There are two more books in this series and I am aching to see if they are as good as this one.

My review really doesn’t do this book justice. There was so much going on that you simply have to experience it for yourself. Beyond the excellent plotting, pace, and characterization, there was actual subtext in this book that didn’t end up being overly moralistic or anything. It actually had some things to say, pretty good things about love and compassion and anger and emotion in general, that I really did not expect to see based on looking at the cover.

The book is definitely a product of the eighties. There are mentions of “Thai-VI ghouls” wandering around. Thai-VI is a fatal sexually-transmitted disease, clearly an analogue of HIV/AIDS, which is interesting to me because 1983 is pretty early on the timeline of HIV awareness. In fact, according to this timeline on Wikipedia, HIV hadn’t even been announced as the cause of AIDS yet, so there you go.

So there’s a good bit of Zeerust in this one and a few cringe-worthy moments regarding both race, gender, and sexual preference, but I’ve read much worse.

Do yourself a favor and see if you can find a copy of this one. If you can, look for the Tor edition from 1991, because it got a much better cover.

If you don’t think that’s an amazing tagline, we probably can’t be pals.